Update_my_research_interests

zying / July 2024 (1618 Words, 9 Minutes)

The brain is a remarkably complex organ, necessitating a multidisciplinary approach to unravel its mysteries. Various disorders, such as intellectual developmental disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and brain cancers, have intricate connections with neuroscience, underscoring the importance of understanding and controlling brain functions. I began my journey of brain exploration by recognizing its complexity (Figure 2) and experiencing various methods to study it.

When it comes to the scientific field, my main interest lies in understanding how heterogeneous cell populations are generated from specific neural stem/progenitor cells (Figure 1A-B). I am particularly focused on identifying the mechanisms that cause these cells to commit to incorrect neurogenesis or gliagenesis (Figure 1E), leading to brain cancer (Figure 1B-C, E) or cortical malformations such as pachygyria (Figure 1D-E). Additionally, I aim to explore how we can manipulate these mechanisms to control cell fate determination as a potential new treatment for related diseases.

Figure 1. The relationships of neural stem/progenitor cells, tumors, and cortical malformations. A. Neurogenesis process. Solid arrows indicate normal development processes; dashed arrows indicate tumorigenesis processes. B. Neural progenitors in adult and fetal stages. C. Glioblastoma shares various pathways with fetal progenitors. D. Potential cell activities forming cortical folding, and the resulting cortical structure malformations when errors occur. E. Balancing stemness maintenance and differentiation through various molecular processes. When the balance favors stemness, the increased proliferation generates numerous progenies, linking both to cortical malformations (specific locations and limited growth ability) and brain tumors (limitless growth ability).

My research experience

Complexity in interneurons. Since the time of Santiago Ramón y Cajal, neuron classification has remained a fundamental area of study in neurobiology. Today, we are empowered by various advanced tools that allow us to observe neurons in greater detail. We can examine their morphology to understand structural differences, study their physiology to learn about their functional properties, and analyze their molecular expression to uncover genetic and biochemical characteristics. These modern techniques enhance our ability to classify and understand the diverse types of neurons within the brain.

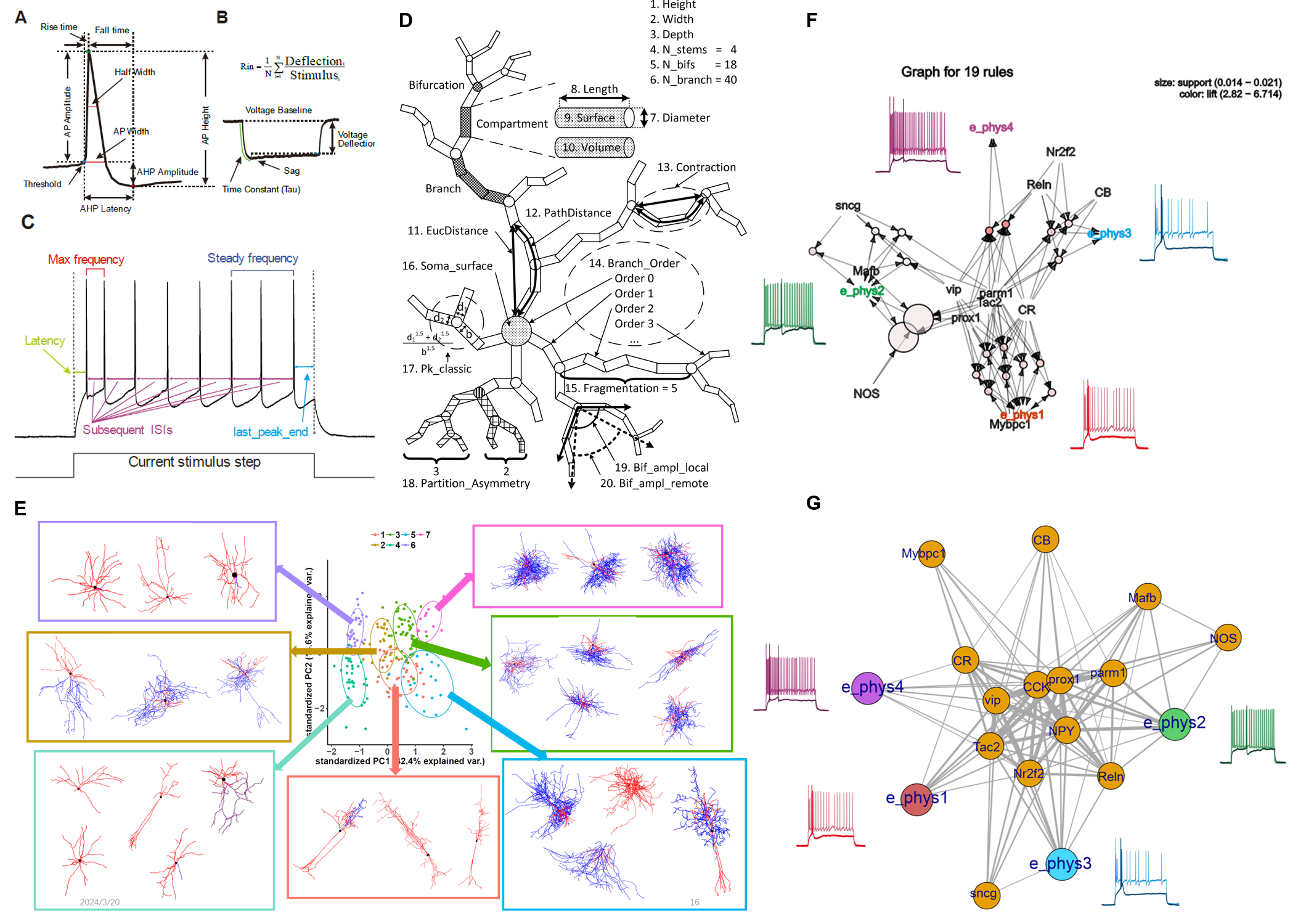

In our project focused on classifying VIP+ interneurons (Shao-Na Jiang, 2023, Poster ), I constructed quantification methods for analyzing the morphology and electrophysiology of neurons (Figure 2A-D) and employed various computational methods to analyze their subtypes (Figure 2F-G). During this research, I thoroughly recognized the complexity of neurons and generated a question: What promotes them to form such complicated features?

Figure 2. My exploration of quantitative neuron electric and morphological features. A-C. Quantitative Electric Parameters. D. Quantitative morphological Characteristics (Costa et al. 2010). E. PCA clustering of morphological features. F-G. Apriori correlation (F) and Complex networking (G) analysis of neuron multi-layer features.

Neural stem/progenitor cells possess the remarkable ability to generate the complex features of neurons and glia. These cells undergo various stages of differentiation and specialization, giving rise to the diverse cell types that contribute to the intricate structure and function of the brain (Figure 1A). Understanding the mechanisms that guide their development is crucial for unraveling the complexities of neural architecture and addressing neurological disorders.

In my previous project on the development of the ferret’s gyrus (Poster), I labeled types of neural stem/progenitor cells and analyzed their differentiation and cell cycle across the gyrus and sulcus regions. This work highlighted the remarkable power of neural progenitors and indicated that exist molecular programme regulating their activity (migration, proliferation and differentiation). While we could not label truncated RGC (tRG), an interesting subtype of radial glial cell (RGC), I learned about them from other published papers, which greatly attracted me. Unlike other neural cells that migrate outward, tRGs truncate their basal process at a particular developmental timeline (Figure 1B). This unique behavior fascinated me and left a strong impression.

Additionally, I learned about a spectrum of diseases linked to cortical malformations, such as pachygyria, from the results of former researchers in this project and my following experience in a hospital-based research platform. Disruptions in cell proliferation, neuronal migration, and postmigrational cortical organization can all result in varied cortical morphologies associated with functional disorders, such as epilepsy, intellectual disability, and autism. These findings underscore that neural stem cells (NSCs) are a vital focus for understanding the brain and developing new treatments for related disorders.

NSC not only exist in the fetal brain. It’s imperative to distinguish between fetal NSCs (fNSCs) and adult NSCs (aNSCs). fNSCs exhibit widespread inside-out multi-layer cellular structures within the fetal brain, whereas aNSCs are primarily located in a dormant state within the subgranular zone (SGZ) and subventricular zone (SVZ) (Figure 1B), becoming activated in response to particular stimuli, such as injury (Noelia Urbán et al. 2019).

There are potential links between NSCs and GSCs. During my bioinformatics Master’s study, I learned about a group of tumor cells in glioblastoma (GBM) that possess the ability to enter a quiescent state and generate various progenies when activated, known as GBM stem cells (GSC). This inspired me to question the relationship between NSCs and GSCs, as well as their corresponding lineages. Therefore, I designed my thesis project that Systematic comparison of GBM and neurodevelopmental trajectories in my bioinformatics Master (Poster). I Integrated and analyzed 5 GBM single-cell/single-nucleus transcriptome datasets, and aligned these datasets with developmental trajectories observed in fetus to systematically compare. The result of tRG showing multiple activation pathways associated with cilia, notably evident in fetal data and broadly activated in GBM (Figure 3), drawn my attention.

Figure 3. Intraciliary transport pathway activation in fetal brain and GBM malignant cells.

When I searched related papers, I gained experiment-validated points: 1) GBMs have been observed to invade the ventricular region, cells in the SVZ secreting factors attracting GBM cells (GBC) towards them (Figure 4A, Qin et al. 2017); 2)a subset of aNSC expressing markers similar to RGC in GBM (Wang et al. 2020). aNSC also shares morphological similarities with tRG (only have apical process, Figure 1B); 3) tRGs generate a significant portion of ependymal cells (Bilgic et al. 2022) that sharing an origin with aNSC (Ortiz-Álvarez et al. 2019).

Given that three hypotheses emerge regarding their origin: 1) mature cells adopting stem-like properties (dashed line in Figure 1A), 2) abnormal differentiation of activated aNSC in response to stimuli resulting tumor cells (Figure 4B), or 3) a combination of the two, wherein the mutations of mature cells trigger an inflammatory response, activating quiescent aNSC, leading to abnormal differentiation into tumor cells (personal hypothesis, Figure 4C).

Figure 4: Potential GBCs, Fetal, and Adult Neural Stem Cell Relationships A. GBMs have been observed to invade the ventricular region, with cells in the SVZ secreting factors that attract GBC towards them (reported by Qin et al. 2017). The red arrow shows the migration direction of GBC; the blue arrow shows the density gradient of the induced factors. B. The hypothesis that abnormal differentiation of activated aNSCs in response to stimuli results in tumor cells. Dashed arrows indicate abnormal differentiation from various aNSCs. The solid arrow shows that when GBM is implanted into the ventricular zone, their invasion towards the ependymal surface is observed. C. The third hypothesis suggests that mutations in mature cells trigger an inflammatory response, activating quiescent aNSCs, leading to their abnormal differentiation into tumor cells.

Overall, I am curious in four questions: 1) Can tRG transition into dormant aNSC residing in the SVZ of adult animals? 2) Is there a mechanism linking aNSC to the generation of GSC? 3) Do GBCs also enter a quiescent state similar to aNSC, and if so, what molecules are involved and how might this relate to recurrence? 4) Can the mechanism for reverting active aNSC back to quiescence and inhibit GBM progression?

Future Goals

I am going to focus on stem/progenitor cells, whether from healthy brains or brain tumors, in adults or fetuses, exploring the molecular mechanisms behind neurogenesis or gliagenesis commitment and their corresponding phenotypic relationships, including electrophysiology, morphology, cell cycle, migration, cell connection patterns, and even behavior patterns. While venturing into the mysteries of the brain is incredibly exciting, my ultimate ambition is to control these mechanisms to improve treatments for CNS diseases in the future.

Technical Expertise

Neuroscience is a multidisciplinary field that employs various technologies and generates vast amounts of data, which are worth mining. The heterogeneity exhibited by a single subtype of neurons in terms of electrophysiological, morphological, and molecular characteristics alone is significant, let alone the complexity of overall brain functions. This far from captures the complexity of the entire brain, especially the developing brain. Therefore, integrating multi-layered data is crucial for further understanding this intricate field. With the rapid accumulation of biological data, I believe our research can be divided into two parts: data collection and data mining.

Data Collection

Data can collect by wet experiments:

- Functional/phenotypic level:

- Behavior: testing using various paradigms, such as forced swimming.

- Electrophysiology in cohort cells: recording via electrode array implantation.

- Brain macro-structure: observing structures like the gyrus through measurements or 3D modeling.

- Transgenic animal models.

- Tissue/cells level:

- Tissue section and staining: including chemical, antibody (IHC), and RNA/DNA probe staining (FISH).

- Imaging: static (2D/3D) and dynamic (time-lapse).

- Cell/tissue culture.

- Virus tracing: considerations include how to inject (e.g., stereotactic injection), where to inject (e.g., subventricular zone or hippocampus), what kind of virus, and the observation timeline.

- Molecular level:

- Genome: WES/WGS, 3D genome (HiC), accessibility (ATAC-seq), methylation (WGBS), TF/histone regulation (CUT&TAG/CUT&RUN/ChIP-seq).

- Transcriptome: bulk/single cell/nucleus RNA-seq, non-coding RNA (microRNA, lncRNA, circRNA, etc.), alternative splicing (AS), alternative polyadenylation (APA).

- Translation: Ribo-seq.

- Bioengineering interference. CRISPR knockouts, RNAi knockdowns and rescuing by artificial adding

Data also can collect from public datasets.

Data mining

-

Data clean and feature extraction

- Electrophysiology or other time sequence data: Extract features such as spike counts, spike shape descriptions, etc. (Figure 2A).

- Morphology or other image data: Preprocess data through denoising, segmentation, reconstruction, and feature extraction (Figure 2B).

- Molecular data: Different pipelines for preprocessing and feature extraction. For example, RNA-seq outputs a differentiated gene list, while ChIP-seq outputs a peak list.

- General approach: Consider the data type and purpose, extract meaningful features, and construct a matrix where rows represent samples and columns represent features.

-

Classification and clustering for pattern recognition

- Discovering correlations across different data layers

- Identify molecular regulation correlations with phenotypes.

- Simulation or modeling for inference or interpretation

Although I conducted various wet experiments in the lab several years ago and mastered them, I now prefer coding and data analysis. I aspire to be a neural data scientist with domain expertise in neuroscience, capable of translating thoughts and problems into meaningful computer language for analysis, modeling, and understanding (as described in (Nylen et al. 2017)).